I apologize for the absence of fresh posts lately. Any teacher knows how the time second quarter can just get away from you, so I won’t try to explain.

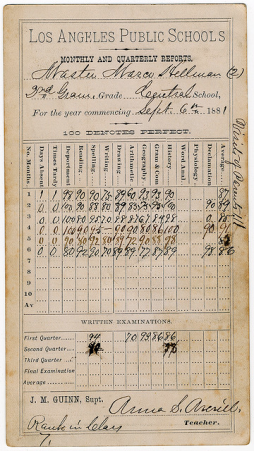

As the quarter closes this week and I enter numbers that turn into the less-specific feedback of letters representing a range of numbers on the report card, I think about what report cards really represent to students and parents.

The last days have been met with so many of the usual questions that teachers get at the end of the quarter:

“Can I have a packet for extra credit?”

- No. Nor may you eat junk food for months and then eat a salad right before the doctor’s appointment and get the same results as the person eating healthily the entire time.

“What can I do to get an ‘A’?”

- Um . . . know more and do more to show that you know it?

“If I do XYZ (turn in this missing assignment, retake the low test grade, etc.) is it possible to get an average of blah-blah?”

- Look, even if you had all the exact numbers in your mythical scenario to give me, I am afraid I could not plug it in with your grades – which I don’t know of the top of my head – and compute the weighted average to give you an answer. So…stop.

What’s frustrating is that the focus in all these questions is how to get the (usually lowest number in the arbitrary range of the) letter grade. Not the learning. Nor the work that should have gone into mastery. Nor the opportunities already missed.

If it’s not on the report card, it does not have meaning or value for parents or students.

Teachers know that work behaviors and effort are very important, probably even more important to a child’s future success than if s/he can diagram a sentence, or solve for x, or find the capital of Belize on a map. Therefore, teachers usually have typically included them in a grade to give them meaning and value. Those behaviors might count for 25% of a class’s grade, or 10%, or “folded in” to each assignment and result in some unknown number.

I’ve done the same. Valuing effort is important.

The problem? A grade as a method of communication to students, parents, universities, and other stake holders in that information is compromised: What does that “B-” mean? A hard worker who doesn’t fully get math – or – a lazy but brilliant math student? It could be either – and it often is.

Here’s my proposed solution: We need to report both content mastery and work behaviors. Equally.

Each class each reporting term should have a content mastery grade AND a work behaviors grade. A student earning an “A/D” knows the material set forth in the standards, but does little in the way of these important behaviors, which he will also need in life. (ie: the lazy AIG child, who does almost nothing but gets an “A” in mastery anyway) However a “C/A” student may struggle with the content, but she works REALLY hard to get that “C” in mastery.

Parents would know an “F/F” on the report card means there’s a reason the child isn’t learning any of the material. An “F/B” however represents a student mostly trying and still failing to grasp concepts. That’s a very different problem. We already know the difference as teachers: parents should know this about their children too. It should be reported to them. It should be reflected on the report card. It should matter.

Work behaviors need a separate grade on a report card so that they are deemed important but the content mastery is still clear.

Thoughts? Rebuttal? Hit me up in the comments!

These have helped me in more than one “What are you doing for my child?” conference and to complete the required intervention plans based on all the data. I don’t know if they have revolutionized me as a literacy teacher, but I suppose

These have helped me in more than one “What are you doing for my child?” conference and to complete the required intervention plans based on all the data. I don’t know if they have revolutionized me as a literacy teacher, but I suppose

If you check grades online or the teacher prints them for you to review, keep in mind that like your bank account, it’s just what’s there at that very moment. Your child’s average is obsolete as soon as another assignment has been collected. Do not panic about that grade that is lower than you’d like, nor “relax” if it’s fine. It’s just that day’s reality, and will change soon. Your efforts are better spent looking at with what types of assignments your child struggles, if there are retake or make up opportunities listed, and if your child is turning work in on time.

If you check grades online or the teacher prints them for you to review, keep in mind that like your bank account, it’s just what’s there at that very moment. Your child’s average is obsolete as soon as another assignment has been collected. Do not panic about that grade that is lower than you’d like, nor “relax” if it’s fine. It’s just that day’s reality, and will change soon. Your efforts are better spent looking at with what types of assignments your child struggles, if there are retake or make up opportunities listed, and if your child is turning work in on time.